Introduction to music from Poitou

Text by Jany Rouger

Historical background

The Poitou was one of the great provinces of France, divided at the time of the 1789 Revolution into three departments: Vienne, Deux-Sèvres and Vendée. The Poitou-Charentes region, encompassing the first two of these departments and the two Charentes, was created in 1956 and has been attached to the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region since 2016.

The former Poitou (including Vendée), Charente-Maritime (combining the former provinces of Aunis and Saintonge), and part of Charente (around Angoulême) constitutes a linguistically homogenous cultural area, where Poitevin-Saintongeais, sometimes called “parlanghe”, was spoken.

Like most Oïl-languages (languages of Latin origin spoken in the north of France, to be distinguished from the Oc-languages spoken in the south), the “Parlanghe” is increasingly losing its everyday use, and is threatened with extinction, like many popular languages around the world, under the blows of cultural standardization. But if the Poitevin-Saintongeais language is in danger, the artistic traditions of the corresponding cultural area, particularly music, seem to be more resistant to cultural massification. Here, we’ll focus on the oral traditions of Poitou, whose vitality is the strongest and most thoroughly researched.

Songs

In the history of this specific culture, most oral music was originally sung : the voice is the most widespread “instrument”, and has always been the medium of everyday artistic expression in working-class circles. The universe of traditional songs is thus extremely vast (the number of versions of traditional French songs can be counted in the tens of thousands), and many researchers have been passionate about collecting and studying them. The first major collection of songs from our region was published in 1864 by Jérôme Bujeaud under the title “Chants et chansons populaires des provinces de l’Ouest”. A few decades later, in the first half of the 20th century, our region gave France one of its greatest song researchers : Patrice Coirault, born and died in Surin, Deux-Sèvres (1875-1959). Starting with a collecting of the very first importance, he set out to find the “antecedents” of traditional songs, i.e. the oldest versions as they might have been notated at a time prior of their oral collection , and masterfully explained the process of creative evolution genrated by oral tradition.

Instrumental music history of Poitou

If song was for a long time the preferred medium for dance, in the tradition of the “chansons à danser” of the Middle Ages, instruments gradually made their appearance in this rhythmic function. No doubt they had been in use for a long time, since Roman church capitals depict a number of musicians, but it was probably during the Renaissance that they came into general use in popular circles.

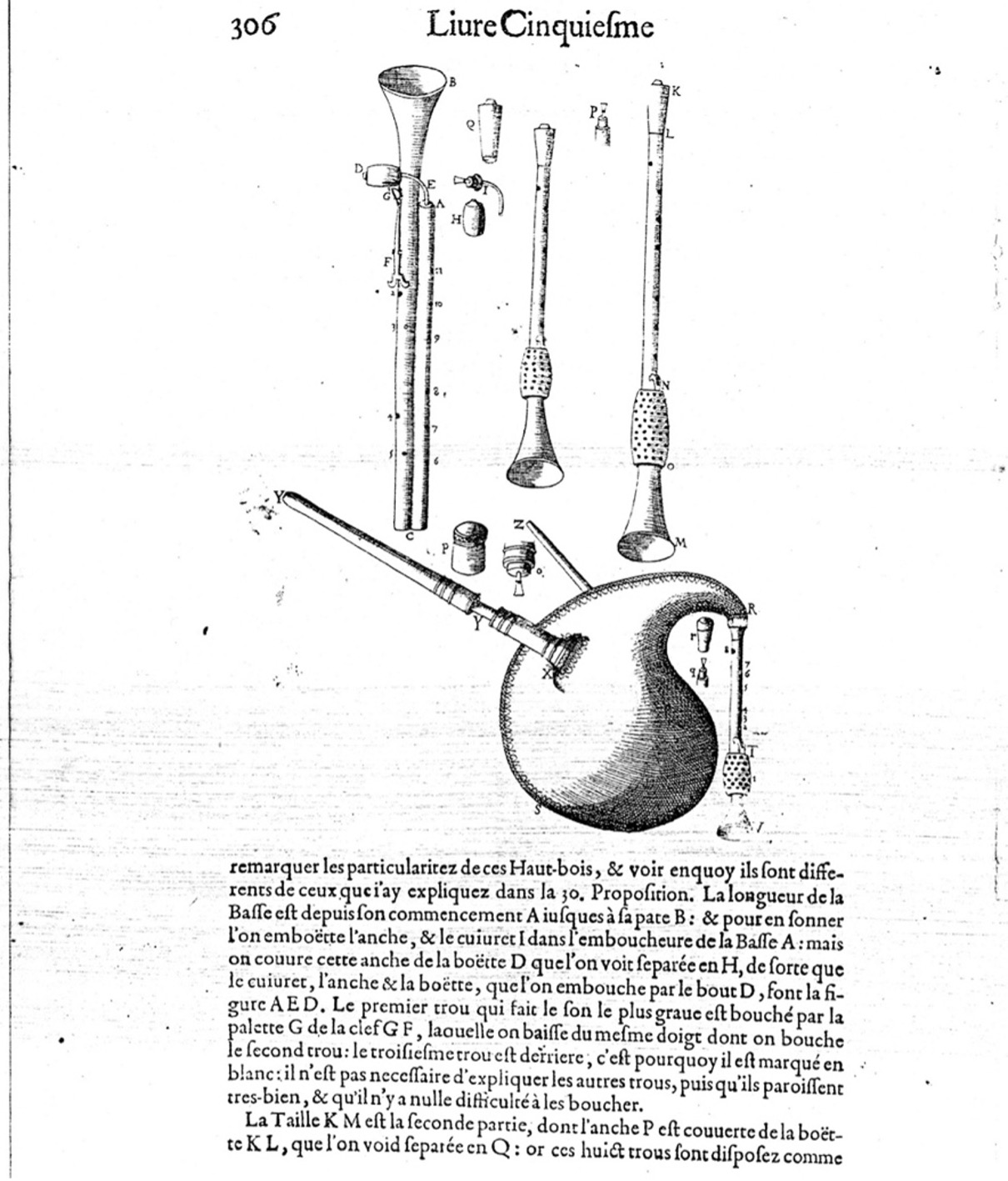

At that time, Poitou was famous throughout the kingdom for the quality of its dancers and musicians, and instruments made in Croutelle, near Poitiers, were exported throughout Europe. This is how Father Marin Mersenne, in his work entitled “L’harmonie universelle” (Universal Harmony), published in 1636, describes the bagpipes and oboes of Poitou, which some chroniclers of the 16th and 17th centuries tell us were played in a “four-part ensemble”, a rare example of popular polyphonic playing.

Marin Mersenne’s L’Harmonie universelle (1636).

At the same time the “violin”1 was already widely used as a dance instrument. The “ménétriers” could just as easily lead the ball with their bow as play a more prestigious instrument (such as the “hautbois”, a “high” instrument) in orchestras set up for major aristocratic or municipal festivities.

While the bagpipe gradually disappeared in Poitou (probably during the 19th century), except in the Marais de Challans (known as “Breton”, but definitely Poitou!) in the form called “veuze”, the fiddle remained the major rural instrument until the First World War. This prevalence gave rise to a specific style common to a large part of the Poitou region, and constitutes one of the major elements of the region’s traditional instrumental music.

Then, from the 1930s onwards, it was supplanted by the chromatic accordion, more powerful and better able to play fashionable tunes. The old repertoires were gradually abandoned.

Other instruments also played a part in this musical history. The diatonic accordion, popularized at the beginning of the 20th century, often remained confined to the family circle or the village eve. The hurdy-gurdy was widespread in eastern Poitou (on the borders of Berry) and more sporadically in the rest of the region; nevertheless, numerous traces of it have been found in Vendée. Instruments imported by wind bands were sometimes adopted by wedding band musicians: the clarinet, from the 19th century onwards; the cornet à pistons to a lesser extent, a little later.

1 The term “violin” was probably used to designate all bowed stringed instruments worn on the shoulder or neck, sometimes much more rudimentary than the violins produced by the great Italian violin makers.

Traditional dance in Poitou

Instrumental history is closely linked to the practice of dance. What are the main features of dance history in Poitou?

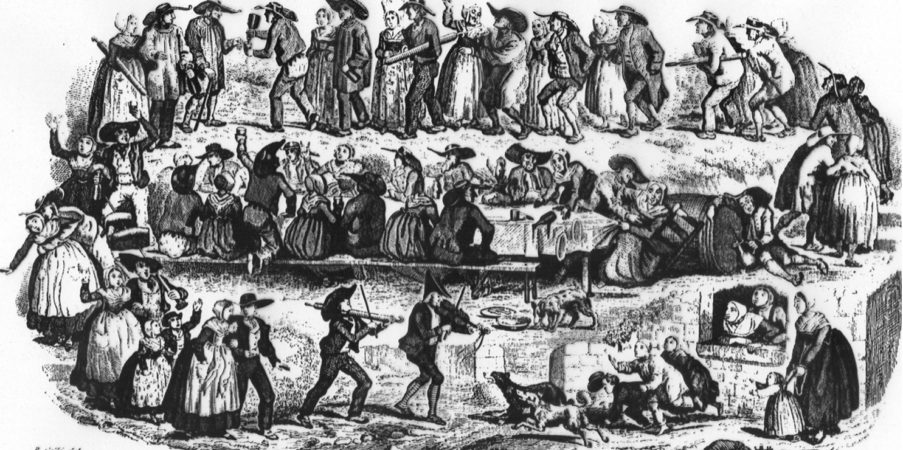

To put it simply, there are several layers of dance forms that have evolved over the centuries, and which can be found, sometimes intermingled, in the repertoires we have collected. The oldest, the legacy of sung rounds dating back to medieval times, has left traces in numerous songs whose rhythmic patterns suggest that they were supports for dance forms. Although these forms had practically disappeared from most Poitevin memories by the time of our collections, apart from a few rondes-jeux (round-games) sometimes danced at village wakes or in schoolyards they had nevertheless retained a strong vitality in certain more isolated territories, such as the island of Noirmoutier or the neighboring Marais, where the dances (rondes or “grand’danses”) were mostly led by voice.

In the centuries that followed, another layer was superimposed, whose form remained round or chain, but whose musical support could call upon instruments: these were the “branles” and other “courantes” (still alive in the Marais de Challans), whose melodies spread throughout our country, and sometimes remained in the memories of our village minstrels.

Because these old tunes were still played, recycling them to create new dance forms : since 18th century, and throughout 19th century, the line replaced the circle, and the contredanse supplanted the chain dance. In addition, the steps of old substrates often remained alive and well, and were used in these new forms. In the lands of the bocage (Vendée and northern Deux-Sèvres), these contredanses became “avant-deux”, “quatre-danses” or “mouvantes”. In the “marches” territories, on the borders of Berry or Limousin (Southern Vienne), a dance related to the bourrée (called “marchoise”) has taken root. Later, the “quadrilles”, which brought together several figures and were therefore more complex in terms of choreography, had lost these complex steps and were simply marched. Then, at the end of the 19th century in the countryside, came the revolution in couple dancing: waltzes, polkas, scottishes and mazurkas became popular, and variants were handed down in all parts of France, including Poitou…

The revival of traditional music

After the Second World War, and even more so in the 1970s, there was a growing awareness of the value of these ancient repertoires and the risk of their disappearance. Various movements for the reappropriation of traditional cultures emerged, not only in France, but also in Europe and North America. The “folk” movement was a direct descendant of the American “counter-culture”. In Poitou, in 1969, popular education activists created a union of associations for the Poitou-Charentes and Vendée regions, the UPCP2, which initiated a vast “operation to rescue peasant oral tradition”, and federated the initiatives of numerous traditional dance, song and music groups. Over the past fifty years, these associations have accomplished a colossal task: more than 10,000 hours of recordings on regional culture have been collected, hundreds of musicians and dancers have been trained, dozens of groups have performed traditional repertoires on the region’s stages, and professional artists enriched on this culture to present it throughout Europe.

Will anyone be surprised by such vitality? That’s because traditional music, the music of memory, exists only through its performers. As music that is constantly being “re-created”, it has always adapted to the times, and is therefore always relevant today. It’s hardly surprising that each generation has been reappropriating them for centuries. No doubt, through them, we rediscover what lies at the very foundation of our sentient being.

2The UPCP-Métive (Union pour la culture populaire en Poitou-Charentes et Vendée) brings together some fifty associations. Its head office is at the Maison des Cultures de Pays, 1, rue de la Vau St-Jacques, Parthenay. See www.metive.org

Some reference singers, instrumentalists and groups

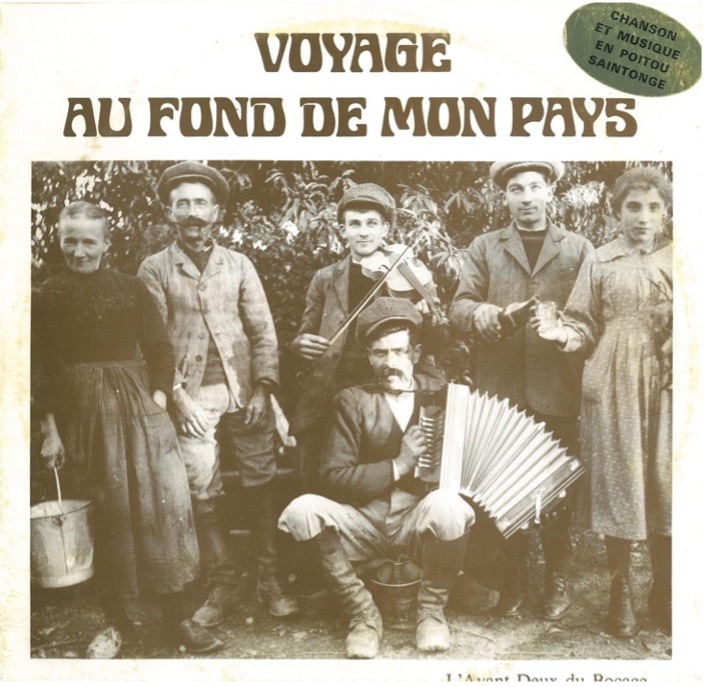

Masters of tradition: since the 1970s, UPCP associations have published numerous records (under the label Geste paysanne, a publishing house set up by the UPCP) featuring the collected musicians: Aimé Bozier, Alcide Guinaud, collection Violons du Bocage (Paul Micheneau, Maximin Rambaud, Alfred Talon), Violoneux de Gâtine, Vielles en Vendée…

The CERDO (Center for studies, research and documentation on orality), created by the UPCP in 1992, has now taken over the baton and publishes a collection of notebooks devoted either to a theme, or to musical personalities. More broadly, CERDO has digitized some of the collections made since the 1970s. They can be found at: https://www.metive.org/cerdo.html

Today’s artists: although Poitou’s artistic scene was abundant from the 1970s onwards (with many well-known amateur groups: les Piboliens, Guillannu, les Brandous, la Marchandelle, Ecllerzie, then later Ardivelle, Amus’trad…), it only became professionalized later, from 1985 onwards: first in the field of storytelling, with great personalities such as Yannick Jaulin, Bernadette Bidaude and Gérard Potier, now recognized nationally.

Then in music, with pioneering groups such as Les p’tits doigts qui touchent, Yole and Buff’Grôl. From these groups, personalities have blossomed: Gérard Baraton, Christian Pacher, Philippe Compagnon, Jean-Marie Jagueneau, Benoit Guerbigny, Sébastien and Thierry Bertrand, Maxime Chevrier and Arbadétorne… A new generation has emerged, trained in associative schools, at the Conservatoire or in higher education: Julien Padovani, Bastien Clochard, Perrine Vrignaud with the group Ma petite…

The UPCP-Métive, through its programming or during the festival “De bouche à oreille“, enables these artists to perform regularly on stage.

Documentary tools:

– Reference films: two films by André Gladu and Michel Brault, part of the famous series “Le son des Français d’Amérique” (classified as Memory of the World by UNESCO): “La terre d’amitié” and “Il faut continuer”, made in 1977 in Poitou. https://www.onf.ca/selection/edu-le-son-des-francais-damerique/

A film by ARCUP (a member association of UPCP-Métive) about one of the groups of the revivalist movement in Poitou, Guillannu:

– Websites and links:

- The database of the Centre d’Études, de Recherche et de Documentation sur l’Oralité (CERDO) of the UPCP-Métive

- Direct access to the page Poitou de la Vinylothèque

- For the Vendée, in addition to the CERDO site, the Arexcpo site

– Most famous current groups:

- Ciac Boum : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bqAoruVl1jw

- Ma petite : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rwH109KpAaI